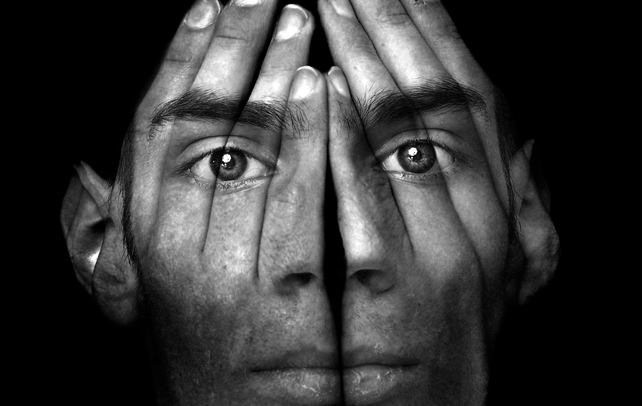

Social anxiety disorder seems to be rooted, as Sartre plausibly pointed out, in the fact that most of what we are is a projection of what others think of us. We should all be afraid of “the look” of another person because it’s an unfathomable abyss into our very essence. And yet, despite its roots in our imagination, social anxiety is an unremittingly “physical” disease. You can have long-term therapy, or read as much philosophy on the subject as you like, but your body won’t care. The next time you interact with another human being on the bus, at the checkout, or on the phone, waves of adrenaline flood your body all the same, resulting in a racing heart, faltering voice and glowing red cheeks.

Current scientific opinion attributes all this to serotonin imbalances and overactive amygdalae. There are also genetic factors at work which try to explain why social anxiety tends to run in families. Whatever the ultimate cause, the stubbornly physical basis of social anxiety suggests that there is no immediate cure. One doctor informed me that it’s just something that has to be lived with. A harsh conclusion indeed, and one that I and other social anxiety sufferers have found to be made much harsher by the nature of the modern world.

It was at this point in my life that I became suicidal. If I couldn’t do small talk, then what chance was there of me ever becoming a functioning member of society? But then I discovered that there exists a place where all manner of oddballs and misfits of the world can be happily accommodated. The City.

There was a firm looking for a trainee broker with enough smarts to manage a bank of clients but not enough gumption to ask uncomfortable questions. They thought I would fit right in. And they were right.

No one cared about who I was or what I was doing that weekend, just as long as I made money, which (hidden behind a phone and computer) I did pretty well. Ironically, shallowness and anomie – an anathema for most right-thinking people – became my nirvana. Dialling phones all day, working long hours, not distracting myself in horseplay. For the first time, it didn’t mean I was weird; it meant I was super-focused.

I think that all of society, and not only social anxiety sufferers, could benefit from a new outlook; one that does not make being the life and soul of the party the ultimate imperative. I felt great relief the moment I decided to stop apologising for being a quiet person who likes doing quiet person things. Such is the nature of social anxiety, that once I accepted who I was, and crucially, let other people know, the weight and shame of the condition evaporated leaving me feeling less, well, anxious. There are still down days, but being truly comfortable with my quietness has at last got me to the stage where the reaction of most people who I tell about my condition is to exclaim: “What? You’re not shy!” – which is as humorous as it is gratifying.

• In the UK, the Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Hotline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is on 13 11 14. Hotlines in other countries can be found here