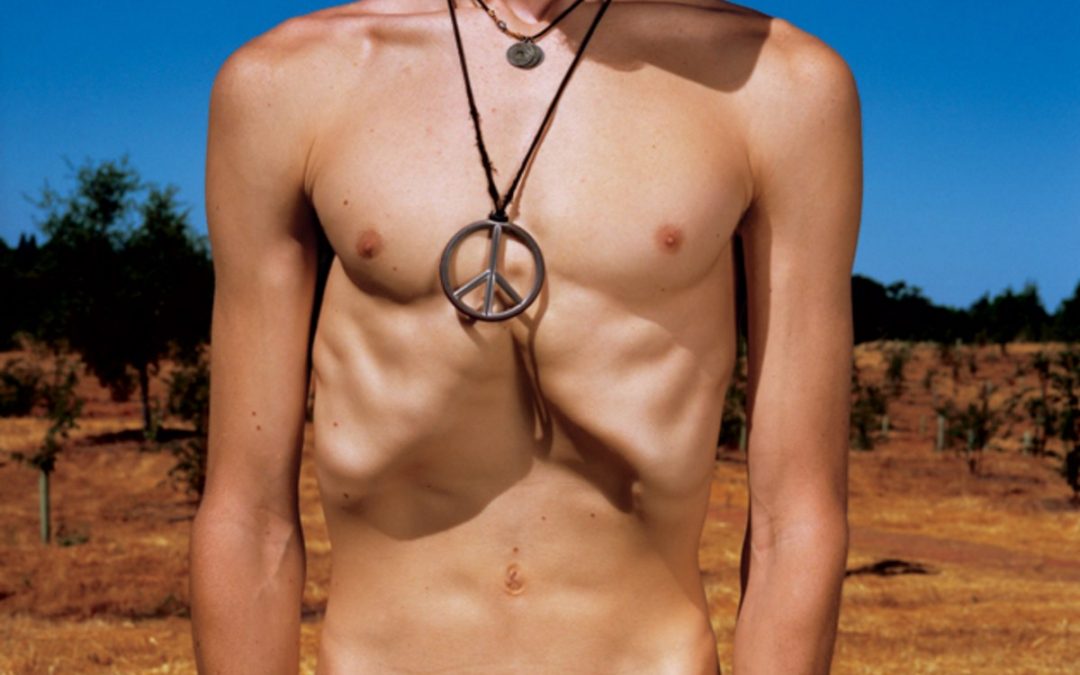

Twenty percent. And rising. More and more men are starving themselves to death in a pathological pursuit of perfection. Male anorexics have much in common with women who suffer from the same debilitating illness, but there’s a striking difference: For the vast majority of men, help is not on the way.

Editor’s Note: Will Brooksbank, one of the young men profiled in this story, died on June 13, 2014 at the age of 22. He had spent exactly half his life battling his anorexia. At his funeral, his family displayed a photograph of him on which they’d printed his final quotation in his section of this article.

A devout Christian, Will was a crusader for his God and his disease. His friends were the anorexics he met during his many hospitalizations, and his family has received many notes from them saying that Will inspired them—that he saved their lives. “He wanted to help everybody else in the world, but he couldn’t help himself,” says his father, Kenn Brooksbank, of San Antonio. Will’s family has established a fund in his name. Contributions can be mailed to the Eating Disorder Center at San Antonio, 515 Busby Drive, San Antonio, Texas, 78209. Checks should be made out to EDCASA, with “Will Brooksbank Fund” indicated in the memo line.

Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness.

No one could possibly watch the hunger artist continuously, day and night, and so no one could produce first-hand evidence that the fast had really been rigorous and continuous; only the artist himself could know that, he was therefore bound to be the sole completely satisfied spectator of his own fast. Yet for other reasons he was never satisfied…. For he alone knew, what no other initiate knew, how easy it was to fast. It was the easiest thing in the world.

— “A Hunger Artist,” by Franz Kafka

I. Steven

280 lbs.

By the time Steven’s girlfriend broke up with him for good, over Christmas of 2009, her bulimia had gotten so severe that her menstrual cycle had stopped. Her doctors in Saskatchewan, Canada, said she might be infertile. To Steven, who had been looking for a piece of land where they could build a house and start a family, the news was devastating. He had gone to family-support days at her residential treatment center, but he says her disease gradually shut him out—that’s what eating disorders do to loved ones. Danielle* had broken up with him over and over again, and each time the pain was unbearable for him. Twice he had tried to kill himself. To drown out the anguish, he had ramped up his partying. Bulimia was her thing, alcohol and cocaine were his.

One night during that long, cold winter, after gorging on two plates of his mother’s lasagna, he went into the bathroom, turned on the shower to cover the sound, and stuck his fingers down his throat. Steven is five feet nine, and he weighed nearly 300 pounds at the time. In the past he had occasionally preempted a hangover by forcing himself to throw up. “It was like a high,” he says. “I felt like I’d gotten away with something. And then I knew that I could do it again, and pretty soon I was throwing up everything I was taking in.” His doctors would later call it trauma bonding—a way of keeping Danielle with him.

Steven has another way of describing it: Getting dumped was like being bitten by a vampire. It turned him into her.

212 lbs.

Steven comes from a family of “patch monkeys”—oil-field workers—and for two years he worked in electrical construction in the oil sands of Alberta, ten days on, four days off. His job was laying down power cable for the well pads. It was exhausting, dangerous work, but if you could hack it, you could make close to six figures straight out of high school.

During winter, the temperature in the oil fields can fall below minus-forty degrees, cold enough for exposed skin to freeze instantly. Steven was risking frostbite when he would slip away into the bush after breakfast and lunch, pull aside his balaclava, and force himself to vomit. He’d kick snow over the steaming pile and hurry back to work. After dinner he’d return to his trailer, turn up his stereo, and puke into his garbage basket. Then he’d toss the bag in a Dumpster.

This became his routine, but the secrecy wore him down. You had to hide the smell. The sound. Soon he found a neater, cleaner way: Instead of purging, he’d just eat less. By the early spring, he was consuming fewer than 400 calories a day—barely 15 percent of the recommended amount for a man of his size and occupation. He was drinking more than ever. In April 2010, after a bender nearly caused him to miss a flight back to the oil field, he checked himself into drug rehab.